A Report on Myocarditis Adverse Events in the U.S. Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System (VAERS) in Association with COVID-19 Injectable Biological Products

Jessica Rose PhD, MSc, BSc and Peter A. McCullough MD, MPH

Link to paper here.

Abstract

Following the global rollout and administration of the Pfizer Inc./BioNTech BNT162b2 and Moderna mRNA-1273 vaccines on December 17, 2020, in the United States, and of the Janssen Ad26.COV2.S product on April 1st, 2021, in an unprecedented manner, hundreds of thousands of individuals have reported adverse events (AEs) using the Vaccine Adverse Events Reports System (VAERS). We used VAERS data to examine cardiac AEs, primarily myocarditis, reported following injection of the first or second dose of the COVID-19 injectable products. Myocarditis rates reported in VAERS were significantly higher in youths between the ages of 13 to 23 (p<0.0001) with ∼80% occurring in males. Within 8 weeks of the public offering of COVID-19 products to the 12-15-year-old age group, we found 19 times the expected number of myocarditis cases in the vaccination volunteers over background myocarditis rates for this age group. In addition, a 5-fold increase in myocarditis rate was observed subsequent to dose 2 as opposed to dose 1 in 15-year-old males. A total of 67% of all cases occurred with BNT162b2. Of the total myocarditis AE reports, 6 individuals died (1.1%) and of these, 2 were under 20 years of age - 1 was 13. These findings suggest a markedly higher risk for myocarditis subsequent to COVID-19 injectable product use than for other known vaccines, and this is well above known background rates for myocarditis. COVID-19 injectable products are novel and have a genetic, pathogenic mechanism of action causing uncontrolled expression of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein within human cells. When you combine this fact with the temporal relationship of AE occurrence and reporting, biological plausibility of cause and effect, and the fact that these data are internally and externally consistent with emerging sources of clinical data, it supports a conclusion that the COVID-19 biological products are deterministic for the myocarditis cases observed after injection.

Keywords

SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, myocarditis, VAERS, adverse events (AEs), COVID-19-Injection-Related Myocarditis (CIRM)

________________________________________________________________________

Background

Myocarditis is inflammation of the myocardium or ‘musculature’ of the heart.1,2,3,4 The myocardium is made up of many cell types however the greatest mass of tissue is accounted for by cardiomyocytes.4,5,6 Cardiomyocytes are the principal contractile cells and are supported by specialized conduction and stromal cell types.4,5,6,7,8 Both systole and diastole are active processes that expend energetic resources of cardiomyocytes which are organized into myofibrils.8,9,10 Myocarditis can manifest as sudden death, chest pain or heart failure. The symptoms of heart failure from myocarditis include effort intolerance, dyspnea, fatigue, and ankle swelling.1,2,3,4,6,11,12,13 The cause is an inflammation of the heart muscle, often following a viral infection, but not exclusively so. The damaged muscle is prone to lethal cardiac arrythmias as well as having the potential to develop both right and left ventricular dysfunction (cardiomyopathy).3,4,12,13

Myocarditis is a major risk for cardiac death among the young.11 The high-risk age population for myocarditis is from puberty through early 30s, and it is the third leading cause of sudden cardiac death in children and young adults. 1 per 100,000 children per year are affected by myocarditis and it has been reported that 0.05% of all pediatric hospitalizations are for myocarditis. Between 0.5 and 3.5% of heart failure hospitalizations are due to myocarditis. Most cases of myocarditis are identified in young adults with males affected more often than females.12,13,14, 15,16

In the context of COVID-19 respiratory illness, there are a significant number of patients who are otherwise healthy experiencing heart-related complications, including myocarditis, but the majority of clinical reports and diagnoses claim cardiac injury based on ICU-related-related injury to the heart.17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25 This is relevant in terms of contextualizing the potential risk of myocarditis from the COVID-19 products against COVID-19 itself and establishing a background rate of myocarditis in specific contexts. Cardiac injuries associated with COVID-19 respiratory illness reveal a set of parameters based on a combination of measurements of troponin levels, electrocardiogram (ECG/EKG), echocardiogram readings, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and clinical symptoms that are different from the clinical picture of vaccine-induced myocarditis. COVID-19-Injection-Related Myocarditis (CIRM) can be defined as the onset of clinical myocarditis that is temporally associated with COVID-19 mRNA or adenoviral DNA vaccine administration and in the absence of another known cause. CIRM presents with clinical symptoms (chest pain, effort intolerance) combined with excessively elevated troponin levels, EKG changes (diffuse ST segment elevation) and in some cases left and right ventricular dysfunction on echocardiography. In cases where the echocardiogram is unrevealing, cardiac MRI can detect changes in tissue characterization consistent with myocardial inflammation.22,23,24,25,26,27

The Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) was created and implemented in 1990 by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to receive reports about adverse events that may be associated with vaccines.28 The primary purpose for maintaining the database is to serve as an early warning or signaling system for adverse events not detected during pre-market testing. In addition, the National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act of 1986 (NCVIA) requires health care providers and vaccine manufacturers to report to the DHHS specific adverse events following the administration of those vaccines outlined in the Act.1 Under-reporting is a known and serious disadvantage of the VAERS system.28,29,30

An Adverse Event (AE) is defined as any untoward or unfavorable medical occurrence in a human study participant, including any abnormal physical exam or laboratory finding, symptom, or disease, temporally associated with the participants’ involvement in the research, whether or not considered related to participation in the research. A serious or severe adverse event (SAE) is defined as any adverse event that results in death, is life threatening, or places the participant at immediate risk of death from the event as it occurred, requires, or prolongs hospitalization, causes persistent or significant disability or incapacity, results in congenital anomalies or birth defects or is another condition which investigators judge to represent significant hazards.28,30,31 These classifications are based on the Code of Federal Regulations. The VAERS handbook states that approximately 15% of reported AEs are classified as severe.28 Myocarditis qualifies as an SAE as it is often associated with hospitalization.

The BNT162b2, mRNA-1273, Ad26.COV2.S products have not been approved or licensed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), having been authorized instead for emergency use by FDA under an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) to prevent Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) for use in individuals 16 years of age and older.232,33,34 Ultimately, the roll-out of COVID-19 injectable biologicals are actively being monitored, but all of the risks are not yet known.16,17,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46

Methods and results

To analyse the VAERS data set the Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, R, was used. The VAERS data set is available for download (https://vaers.hhs.gov/data/datasets) in three separate comma-separated values (csv) files representing i) general data for each report; ii) the reported AEs or ‘symptoms’, and iii) vaccine data including vaccine manufacturer and lot number, for each report. The VAERS dataset is updated approximately once a week and the uploaded set is approximately one week behind the reports. Upon individual reporting of vaccine side effects or adverse events, a VAERS ID number is provided to the individual to preserve confidentiality, and a detailed description of the side effects are transcribed along with the individual's age, residence by state, past medical history, allergies and gender and many other details. In addition, the vaccine lot number, place of vaccination and manufacturer details are included in the report. In order to maximize the input variables for my analysis, the three files were merged by VAERS ID that is included as a linking variable in all three files. The merged data set comprises data collected pertaining to all reported AEs associated with BNT162b2, mRNA-1273, and Ad26.COV2.S products: the three primary vaccine manufacturers responsible for nCoV-2019 products currently being administered in the U.S. Data was sorted according to vaccine type (data reported for COVID-19) and relevant variables were sorted including VAERS ID, AEs, age, gender, state, vaccination date, date of death, incident of death, dose series, treatment lot number, treatment manufacturer, hospitalizations, emergency department visits and onset date of AEs. Myocarditis as a standalone AE was extracted by keyword and cardiac events were grouped by extracting multiple keywords according to MedDRA nomenclature. Statistical analysis was done using the Student's t-Test to determine statistically significant differences between ages in the myocarditis AE. Skewing in distribution of data was tested using Pearson's Skewness Index, I, which is defined as I = (mean-mode)/standard deviation. The data set is significantly skewed if |I|≥1.

Results: General information

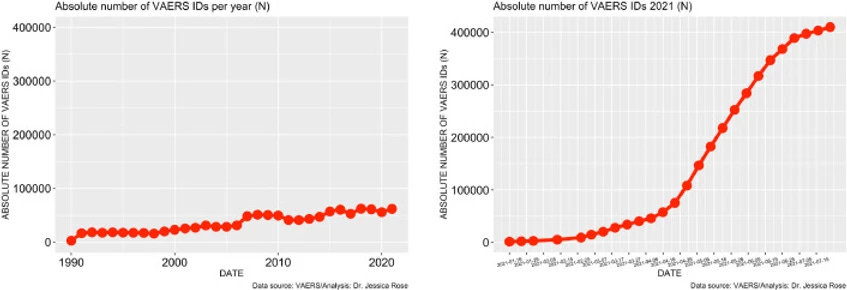

To date, approximately 56% of the total US population has been ‘fully vaccinated’ against COVID-19. As of July 9th, 2021, 397,262 AEs have been reported in the VAERS system. This number is very atypical and large when compared to frequencies of AE reports from previous years. Figure 1 illustrates the stark contrast between what the count would be if the trend of past 30 years continued through to the end of 2021: ∼65,000 for the entire 2021 year as opposed to ∼400,000 over 6 months. There are almost 4,000 different AE types reported (to date) in the context of COVID-19 products and among them, many SAES. As previously stated, the VAERS handbook maintains that ∼15% of all the AEs should classify as SAEs yet the percentage holds at 18% for COVID-19-related AEs.

Download : Download high-res image (330KB) Download : Download full-size image

Figure 1. Time series plots – all VAERS reports in association with all vaccines administered to the U.S. population by year (left) and VAERS reports in association with COVID-19 products for 2021 (right).

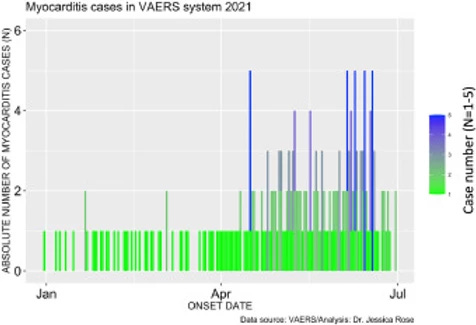

Among these SAEs are cardiac AEs that include cardiac arrest, myocardial infarction, and myocarditis. Myocarditis reports in the context of the COVID-19 products are atypically high in the context of prior vaccine rollouts and in the context of baseline levels with respect to high-risk groups. The number of cases of myocarditis reported to the VAERS database dramatically outnumber case counts seen in previous years with 1 single case having been reported in 2019 and 1 single case being reported in 2020 (Refer to Section 1.4). Figure 2 shows the absolute numbers of myocarditis cases reported for 2021 as per Onset Date. It is clear from this bar plot that the frequency of myocarditis cases reported to VAERS has increased starting at the beginning of June. This is just shortly after the roll-out of injections into children aged 12-15 began. On May 10, 2021, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for BNT162b2 vaccine in children aged 12-15. Of note, 67% of myocarditis cases were in the context of administration of BNT162b2.

Download : Download high-res image (197KB) Download : Download full-size image

Figure 2. Bar plot showing the number myocarditis cases reported from January 1st to July 9th, 2021.Incidence rates of myocarditis in youths

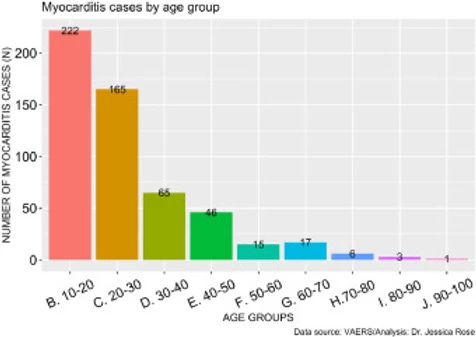

As of July 9th, 2021, a total of 559 myocarditis AEs (0.14% of all AEs) have been reported. Of the reports, 80% of the gender classification was male. In general, 71% of all VAERS reports are made by females so this statistic is particularly telling. The increase in myocarditis reports coincides with the COVID-19 injection rollouts in children aged 12-15, thus, we hypothesized that the increased cases of myocarditis were in fact occurring in children of these ages. Figure 3 shows the distribution of myocarditis cases by age grouped by decade. 41% of all myocarditis reports were made for children aged 10 through 20 and 72% of all myocarditis reports were made for young adults aged 10-30 years of age. The distribution is right-skewed toward the younger age groups, and this is statistically significant (I=1.61). This provides strong evidence to support our hypothesis.

Download : Download high-res image (148KB) Download : Download full-size image

Figure 3. Histogram showing the number of reported VAERS cases of myocarditis by age group.

As of May 18th, 2021, 600,000 children aged 12-15 had been injected with COVID-19 products3.14 The CDC estimated that 3,430,741 children aged 12-15 have received at least one dose of the COVID-19 products as of June 7th, 2021.4 Since 1 per 100,000 children per year are affected by myocarditis5 then, statistically, we would expect ∼5 myocarditis cases if we calculate the expected number of cases using the June 7th CDC sample. To date (up to and including July 2nd, 2021), 97 children aged 12-15 have had reports submitted to VAERS representing 17.4% of all myocarditis reports – and these are merely the cases that we are aware of. Thus, after 8 weeks of roll-out into the 12-15 years-old age group, we are at ∼19 times the expected number of cases within this sample. Thus, the number of VAERS-reported cases far outnumber what would typically be expected to date. It is important to note that of the 559 myocarditis VAERS reports, 6 died (1.1%) and 33% of these deaths were in individuals under 20 years of age: 1 individual was 13 and one was 19 years of age.

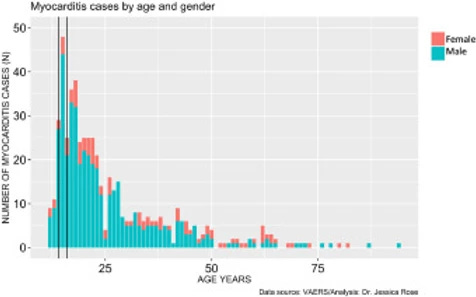

Data right-skewed in statistically significant way toward young males

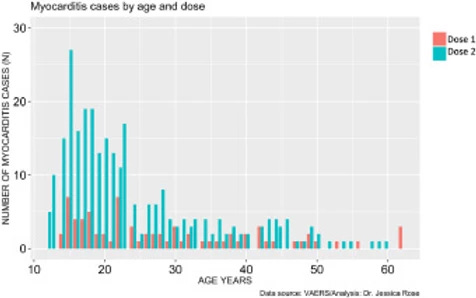

In addition to very high rates of myocarditis cases in children aged 12-15, these rates are observed much more commonly in males. Figure 4 shows the distribution of myocarditis cases by age in males versus females. The distribution is right-skewed toward the younger age groups, and this is statistically significant (I=1.28), and males represent 80% of all cases. The most frequent occurrences were in 15-year-old boys (N= 44) and 18-year-old girls (N= 6).

Download : Download high-res image (137KB) Download : Download full-size image

Figure 4. Histogram showing Myocarditis cases reported in VAERS following injection with COVID-19 products according to age and gender.

Acute myocarditis following 2nd dose

The prevalence of myocarditis reports in the VAERS system is much higher in the context of dose 2 when comparing by age (t-test: p-value = 0.00092) and more highly associated with BNT162b2 (74% of all dose 2 reports are in the context of BNT162b2. It is also much higher in males when comparing by age (t-test: p-value = 0.000009). Dose 2 is generally administered 3 weeks following the first dose assuming the individual survives dose 1 without any major complications, including death. The BNT162b2 maintains a 21-day interval between dose 1 and 2 while the mRNA-1273 maintains a 28-day interval.6 Figure 5 reveals that myocarditis reports peak in frequency at 6X for dose 2 in 15-year-old males. It also reveals that regardless of age, myocarditis cases are more frequently reported following dose 2.

Download : Download high-res image (142KB) Download : Download full-size image

Figure 5. Histogram showing Myocarditis cases reported in VAERS following injection with COVID-19 products according to age and dose.

Since the high-risk age population for myocarditis is from puberty through early 30s, myocarditis should be considered diagnostically in any young adult who experiences shortness of breath, palpitations or chest pain following injection with dose 1 of any COVID-19 injectable product. It is notable that chest pain is a prevalent tandem AE (25% of individuals who filed myocarditis reports into VAERS also experienced chest pain following dose 1) and this may not be acknowledged by a teenager, or even a medical professional, as a warning sign of cardiac insult. The data is right-skewed toward the younger ages, and this is statistically significant (I=1.2).

COVID-19 products highly associated with myocarditis – a case for causation?

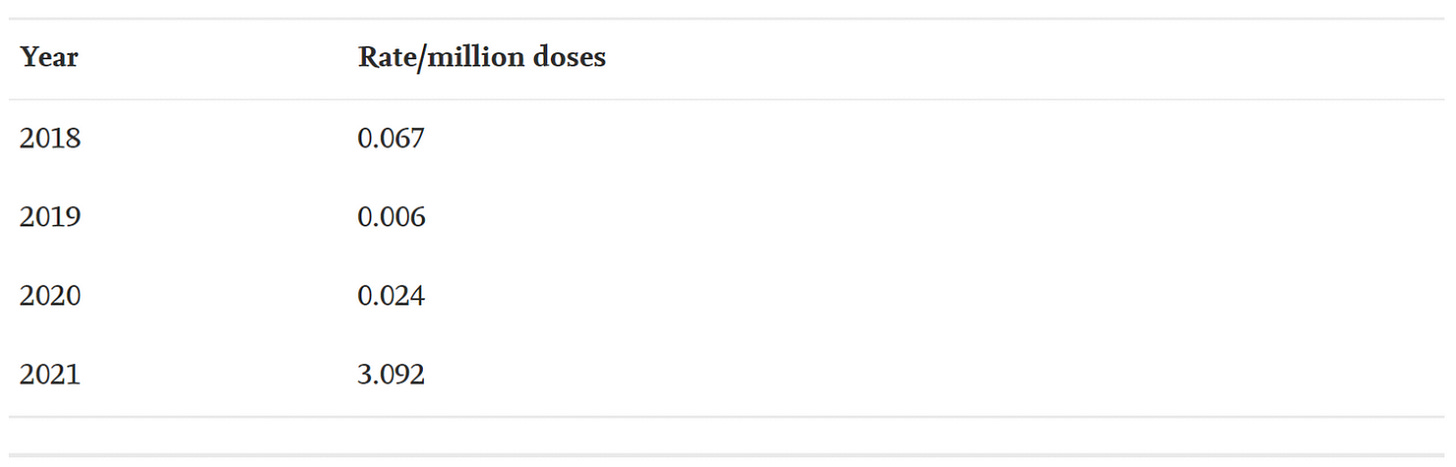

About 1.5 million cases of acute myocarditis occurred in 2013. In 1990, 294,000 individuals died from cardiomyopathy (including myocarditis) which increased to 354,000 deaths in 2015. Myocarditis is a rare disease and typically presents in males and younger individuals as previously stated. The trigger for myocarditis is considered idiopathic but generally thought to be the result of infection or toxin.2 However, in the context of vaccine-induced myocarditis, report numbers have typically been very low. That is, however, until recently. Consider that 2021 is the only year we have been able to collect AE data for the COVID-19 products and prior years are exclusively non-COVID products, except for 2 weeks in December 2020.

The average number of myocarditis reports in VAERS in the context of all vaccines combined for the past 3 years is 4: 11 (0.02% of total) reports were made in 2018, and 1 report was made for 2019 (0.002% of total) and 2020 (0.002% of total), respectively. The number of myocarditis case reports for 2021 are at 559 (0.14%); far higher than last year for all vaccine products combined as shown in Figure 6. Myocarditis case rates for 2018-2021 reveal that the rates of myocarditis, when normalized to the number of fully vaccinated/injected individuals, are exceedingly higher in 2021 than for previous years as shown in Table 1.

Download : Download high-res image (110KB) Download : Download full-size image

Figure 6. Bar plot showing Myocarditis cases reported in VAERS by year. *2021: up to and including July 9th, 2021.

______________________________________________________________________________________________

Table 1. Case rates of myocarditis per year based on estimated number of doses per year with respect to the population size for the season normalized to the number of doses administered per vaccine. *Population data extracted from Worldometer9 and vaccine data extracted from Our World in Data10 and CDC database11.45,46,48

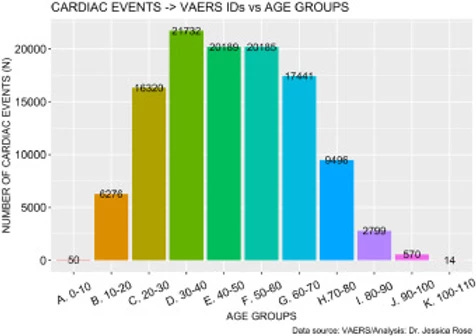

Cardiac events associated with COVID-19

There are 129,522 AEs to date (July 9th, 2021) that are directly related to clinical diagnosis of serious cardiac issues such as myocarditis. These AEs are shown Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 whereby Supplementary Table 1 shows clinical effects such as chest pain and pericarditis and Supplementary Table 2 shows clinical markers or diagnostic elements such as elevated Troponin and Fibrin D dimer levels. This number was calculated using a function that extracts field entries from the VAERS updated AE dataframe that match the list, and subsequently counts them. Figure 7 shows the distribution of cardiac events by age group generated just from this short list of keywords. The highest number of reports was made by individuals aged 30-40 but overall, the distribution is symmetric and unimodal with no statistically significant skewing toward any specific age group (I=0.32). This means that cardiac AEs are being heavily reported, regardless of age.

Download : Download high-res image (177KB) Download : Download full-size image

Figure 7. Histogram showing Cardiac cases reported in VAERS by year.

______________________________________________________________________________________________

Discussion

In the context of COVID-19, and according to Dr. Leslie Cooper, there are a significant number of patients who present clinically as healthy who are experiencing heart-related complications, including myocarditis. 72,17,18,19 There is a high risk of cardiac involvement both from COVID-19 infection and from COVID-19 injectable products and the risks of the latter must be further assessed and evaluated. Because of the spontaneous reporting of events to VAERS, we can assume that the cases reported thus far are not rare, but rather, just the tip of the iceberg. Again, under-reporting is a known and serious disadvantage of the VAERS system.28,29,30 The only way to understand how common myocarditis is after COVID-19 vaccination, is to perform a prospective cohort study where all vaccinated individuals undergo clinical assessment, ECG, and troponin measurement at regular intervals post-administration.

The fact that the VAERS reporting of myocarditis is 6X higher in 15-year-olds following dose 2 may be indicative of a cause-effect relationship. If we assume that following dose 1, a certain percentage of healthy young males who lack co-morbidities or co-factors experience cardiac-related AEs mild enough so as not to dissuade them from receiving dose 2 (ie: pallor, chest pain and shortness of breath, for example), then it is not difficult to imagine that they may have been experiencing symptoms of myocarditis. If a percentage of young males had experienced primary damage to the heart as a result of inflammation following dose 1, then dose 2 may have induced a much more noticeable clinical impact, or cardiac ‘insult’. In other words, these young males may receive a definitive diagnosis of myocarditis only following dose 2. What this implies, based on these assumptions, is that if there is a causal relationship then it might manifest with overlooked/unreported AEs following dose 1 and a diagnosis of myocarditis following dose 2. It is noteworthy that ‘Vaccine-induced myocarditis’ was in fact used as the descriptor by medical professionals as the reason for the myocarditis in the VAERS database.

During phase III clinical trials for the mRNA COVID-19 products, safety was assessed based on a maximum observation period of 6 months. This is not adequate to assess long-term safety outcomes as it is a requirement, even in an accelerated timeline setting, to spend up to 9 months in Phase III trials.8 The typical timeline is up to 10 years for safety and efficacy assessment.47,48 There are many examples of biological product recalls historically. In 2010, rotavirus vaccines licensed in the U.S were found to contain Porcine circovirus (PCV) type 1 and were subsequently suspended. In 2009, an increased risk of narcolepsy was found following vaccination with a monovalent H1N1 influenza vaccine that was used in several European countries during the H1N1 influenza pandemic. Between 2005 and 2008, a meningococcal vaccine was suspected to cause Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS). In 1998, a vaccine designed to prevent rotavirus gastroenteritis was associated with childhood intussusception after being vaccinated. Also in 1998, a hepatitis B vaccine product was linked to multiple sclerosis (MS).49 It is also vital to address that pregnant woman were in the exclusion criteria list for the Phase III trials (ref: NCT04368728) and thus it is unclear how a safety assessment can be made for pregnant women when the products were only tested for 6 months.50 In this context, it is worth reiterating that BNT162b2, mRNA-1273, and the Ad26.COV2.S products have not been approved or licensed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), having been authorized instead for emergency use by FDA under an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) to prevent Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), and was originally meant for use in individuals 16 years of age and older.32,33,34 mRNA platforms have never before been implemented for use in human subjects on a global scale in the context of viruses and it has recently been shown that the spike protein itself systemically traffics inducing damage within cells, at the cell surface, and through circulation with endothelial damage and thrombosis.44,45 It is unknown which cells and organs are seeded with mRNA, the cellular half-life of the products, duration of spike protein production, reverse transcription, future regulation, and ultimate disposal of mRNA technology.51,52 Safety is always a point of relevance with regards to new biological agents and given these new findings, it would be prudent to pay particular attention to the AEs being reported to the VAERS system in the context of these experimental products with known dangerous mechanisms of action. When evidence of harm appears, we need to follow the evidence and immediately take steps to mitigate risks.

Based on this study, the risk of suffering myocarditis subsequent to injection with the mRNA-based products is low with an average of 4 individuals suffering myocarditis per million fully injected. However, the Israeli Ministry of Health recently announced that approximately 1 in 4,500 men ages 16 to 24 who received BNT162b2 developed myocarditis.46 This rate is much higher than the rate estimated based on VAERS data and could reflect variation in reporting. Nonetheless, the risk is higher for the young with an average of 28 12-15-year-olds succumbing to myocarditis per million fully immunized. Discerning between ICU-related mild cardiac injury with SARS-CoV-2 respiratory infection and myocarditis in the context of COVID-19 and the injectable biologicals is important. In establishing background rates of myocarditis in the context of both COVID-19 and injection-associated cardiac injuries, it is vital to ensure that true myocarditis is ensuing for diagnostic purposes. This can be achieved by definitively quantifying the levels of markers for myocarditis such as troponin (I and T), EKG/echocardiograms, and detecting deviations in ST and T waves, PR and QT intervals and T wave inversion. Changes the overall area under the curve for cardiac troponin, reductions in left ventricular ejection fraction, and changes in tissue characterization by cardiac MRI can also be used as diagnostic quantifiers to aid in discerning between CIRM and ICU-related cardiac injuries. As a general rule, the ICU cardiac injury described in COVID-19 illness is subclinical and largely reflected by a minor elevation of cardiac troponin, whereas CIRM is characterized by a clinical syndrome often warranting hospitalization, dramatic ECG changes, and very large elevations of cardiac troponin that are sustained over time.53,54,55,56,57,58,87

It is vital to recall that children have a negligible risk for COVID-19 respiratory illness, and yet they are a high-risk group for myocarditis with vaccination. Newly-published evidence of Vaccine-Induced Autoimmune Myocarditis,58 demonstrates the risks of myocarditis associated with vaccination.87,88,89,92,93,94,95 Despite this, a recent CDC report (May 31, 2021) claimed no danger signal was detectable from the VAERS AE data in the context of myocarditis and as such, they continue to support administration of these products into children 12 years of age and older despite reports of myocarditis and pericarditis in youth in temporal proximity to dose administration.94

It possible that vaccine-induced myocarditis is amplified by prior infection and pathogenic priming. Higher uptake of genetic material in some younger individuals who have been previously recovered from COVID-19 and were vaccinated, may partially explain why some individuals suffer from CIRM and others do not. Nevertheless, the background rate for children aged 12-15 has been established outside of the COVID-19 context and the rates in the context of CIRM are 19 times higher than the expected value.

A recent study shows increased myocardial ACE-2 expression in individuals with ‘basic heart failure disease’ indicating an intrinsic susceptibility of the heart to SARS-CoV-2 infection and worse prognosis.55 Another study in Hypertension from 2008 claims that cardiac over-expression of ACE-2 exerts protective influence on the heart during myocardial infarction by preserving left ventricular wall motion and contractility, and by attenuating LV wall thinning.56 However, we postulate the pathogenesis of CIRM must be much different with isolated production of spike protein over a sustained period of time and expression of the cell surface of cardiomyocytes, which would be considerably different than virion replication. The implications are the ACE-2 expression probably plays a smaller role in vaccine-induced myocardial injury and it has been noted by the co-author that the latter is more highly-associated with maintained elevated troponin levels. [unpublished clinical findings]

Additional information may be gleaned from routine EKG readings and cardiac troponin measurement in volunteers post-injection. It is unknown if in-situ production or perfusion with blood carrying spike protein are the major mechanisms by which CIRM is initiated. Once, damaged, inflammation in the myocardium may last for weeks or months after the original insult is removed.55,58 The exact mechanisms of action for induction and progression of CIRM needs to be elucidated to ensure improved and safer products for the future.

The clinical implications of acute myocarditis in younger individuals as a result of uncontrolled production of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein within cardiac myocytes and cardiac support cells is unknown. If myocarditis has developed after the first injection, then second administrations and boosters should be avoided. Sustained elevations of cardiac troponin, reduction in left and right ventricular function, large areas of inflammation or scar on imaging, and cardiac arrhythmias all portend a poor prognosis for the development of heart failure and cardiac death. Because the duration of action of genetic material coding for spike protein is unknown, follow-up with cardiology consultation is advised in all cases and repeat imaging and biomarkers is wise. Empiric treatment with renin-angiotensin system inhibitors and evidence-based beta-blockers is advised for those at risk for or with manifest left ventricular dysfunction.

Conclusions

These data are derived from a rushed, non-FDA-approved, ongoing investigational product roll-out, and our conclusions are thus limited by the information at hand. In addition to the 12-15-year-old age group data being very early, it is vital to acknowledge that these reports represent a fraction of the actual total. Thus, due to both the problems of under-reporting and the known lag in report processing, this analysis reveals a strong signal from the VAERS data that the risk of suffering CIRM – especially males is unacceptably high. Again, children are not a high-risk group for COVID-19 respiratory illness, and yet they are the high-risk group for CIRM.

Efficacy of these products needs to be assessed by immunological assays and long-term studies are required, while safety needs to be evaluated by rigorous clinical, laboratory and imaging assessments of severe reported adverse events such as CIRM. Autopsies should be done in cases of cardiovascular-related deaths temporally associated with COVID-19 injectables. It is reasonable to use the precautionary principle in this particular setting since an alarming number of reports are coming from young males between the ages of 12 and 15. Boys of these ages should be carefully monitored for warning signs of myocarditis which many may pass off such as pallor, chest pain, shortness of breath or lethargy, following dose 1 with the aim of seeking prompt evaluation and avoiding dose 2.

Effective multidrug therapy is available for rare case of serious COVID-19 respiratory illness in the forms of antivirals, immunomodulators, and anthrombotics.59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72 The combination of a low IFR in children indicating effective and robust immune responses73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83, and the ability to treat with medical therapy, should the need arise, bodes well for clinical outcomes in children69,70,71,72.

As part of any risk/benefit analysis which must be completed in the context of experimental products, the points herein must be considered before a decision can be made pertaining to agreeing to 2-dose injections of these experimental COVID-19 products, especially into children and by no means, should parental consent be waived under any circumstances to avoid children volunteering for injections with products that do not have proven safety or efficacy.

Future work may include on-site clinical observations of Troponin, BNP, galectin-3, ST2, IL-6 and D-dimer levels to corroborate temporal effects of onset of myocarditis following injections with particular COVID-19 products. Delineation between COVID-19 respiratory infection with mild ICU-related cardiac injury and true CIRM using these and other clinical diagnostic markers would be incredibly useful for clinicians and should become the standard for differential diagnosis of suspected CIRM. Correcting the inherent limitations of the VAERS dataset must be a priority as part of future studies. Incomplete VAERS dataset field entries describing prior COVID-19 infection and diagnostic tests such as cardiac MRIs in individuals diagnosed with myocarditis, for example, would make this particular study even more potent. However, despite these limitations, and the limitation of using the VAERS dataset for studies like this one, the usable sample sizes have good statistical power. Ultimately, it remains vital to share the results herein to allow true pharmacovigilance to take place.

Author's contributions

Dr. Jessica Rose completed the data analysis and wrote and edited the manuscript.

Dr. McCullough provided critical edits and content.

References

1. Cooper LT Jr. Myocarditis. N Engl J Med. 2009 Apr 9;360(15):1526-38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0800028. PMID: 19357408; PMCID: PMC5814110.

2. National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/myocarditis/

3. Sinagra G, Merlo M, Pinamonti B, editors. Dilated Cardiomyopathy: From Genetics to Clinical Management [Internet]. Cham (CH): Springer; 2019.

4. ESC Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine, 3rd edition

5. Libby P, Swirski FK, Nahrendorf M. The Myocardium: More Than Myocytes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Dec 24;74(25):3136-3138. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.10.031. PMID: 31856970.

6. Tran DB, Weber C, Lopez RA. Anatomy, Thorax, Heart Muscles. [Updated 2020 Sep 19]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bookb/NBK545195/

7. Banerjee I, Fuseler JW, Price RL, Borg TK, Baudino TA. Determination of cell types and numbers during cardiac development in the neonatal and adult rat and mouse. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007 Sep;293(3):H1883-91. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00514.2007. Epub 2007 Jun 29. PMID: 17604329.

8. M.F. Wendt-Gallitelli, G. Isenberg. Electrophysiology and Microinjection. Methods in Neurosciences, 1991.

9. https://www.britannica.com/science/myocyte

10. Weinhaus A.J., Roberts K.P. (2009) Anatomy of the Human Heart. In: Iaizzo P. (eds) Handbook of Cardiac Anatomy, Physiology, and Devices. Humana Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-60327-372-5_5.

11. Harris KM, Mackey-Bojack S, Bennett M, Nwaudo D, Duncanson E, Maron BJ. Sudden Unexpected Death Due to Myocarditis in Young People, Including Athletes. Am J Cardiol. 2021 Mar 15;143:131-134. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2020.12.028. Epub 2020 Dec 19. PMID: 33347841.

12. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/myocarditis/symptoms-causes/syc-20352539

13. Myocarditis Education Updates and How to Potentially Diagnose the Disease. Aug 4, 2020. Myocarditis Foundation

14. Myocarditis in children: incidence, clinical characteristics and outcomes. Jul 29, 2020. Myocarditis Foundation

15. https://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/myocarditis.htm

16. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/safety/myocarditis.html

17. Siripanthong B, Nazarian S, Muser D, et al. Recognizing COVID-19-related myocarditis: The possible pathophysiology and proposed guideline for diagnosis and management. Heart Rhythm. 2020;17(9):1463-1471. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.05.001

18. Mele D, Flamigni F, Rapezzi C, Ferrari R. Myocarditis in COVID-19 patients: current problems. Intern Emerg Med. 2021 Jan 23:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s11739-021-02635-w. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33484452; PMCID: PMC7823176.

19. Castiello T, Georgiopoulos G, Finocchiaro G, et al. COVID-19 and myocarditis: a systematic review and overview of current challenges [published online ahead of print, 2021 Mar 24]. Heart Fail Rev. 2021;1-11. doi:10.1007/s10741-021-10087-9.

20. Albert E, Aurigemma G, Saucedo J, Gerson DS. Myocarditis following COVID-19 vaccination. Radiol Case Rep. 2021;16(8):2142-2145. doi:10.1016/j.radcr.2021.05.033.

21. How Can COVID-19 Affect the Heart? Aug 18, 2020. Myocarditis Foundation

22. Montgomery J, Ryan M, Engler R, Hoffman D, McClenathan B, Collins L, Loran D, Hrncir D, Herring K, Platzer M, Adams N, Sanou A, Cooper LT Jr. Myocarditis Following Immunization With mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines in Members of the US Military. JAMA Cardiol. 2021 Jun 29. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2021.2833. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34185045.

23. Martinez MW, Tucker AM, Bloom OJ, Green G, DiFiori JP, Solomon G, Phelan D, Kim JH, Meeuwisse W, Sills AK, Rowe D, Bogoch II, Smith PT, Baggish AL, Putukian M, Engel DJ. Prevalence of Inflammatory Heart Disease Among Professional Athletes with Prior COVID-19 Infection Who Received Systematic Return-to-Play Cardiac Screening. JAMA Cardiol. 2021 Jul 1;6(7):745-752. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2021.0565. PMID: 33662103; PMCID: PMC7934073.

24. Puntmann VO, Carerj ML, Wieters I, Fahim M, Arendt C, Hoffmann J, Shchendrygina A, Escher F, Vasa-Nicotera M, Zeiher AM, Vehreschild M, Nagel E. Outcomes of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Patients Recently Recovered From Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol. 2020 Nov 1;5(11):1265-1273. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.3557. Erratum in: JAMA Cardiol. 2020 Nov 1;5(11):1308. PMID: 32730619; PMCID: PMC7385689.

25. Gregorio Tersalvi, MD, Marco Vicenzi, MD, Davide Calabretta, MD, Luigi Biasco, MD, PhD, Giovanni Pedrazzini, MD, Dario Winterton, MD. Elevated Troponin in Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019: Possible Mechanisms. Review article| Volume 26, ISSUE 6, P470-475, June 01, 2020. Published:April 18, 2020DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2020.04.009.

26. Nascimento JHP, Gomes BFO, Oliveira GMM. Cardiac Troponin as a Predictor of Myocardial Injury and Mortality from COVID-19. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2020 Oct;115(4):667-668. English, Portuguese. doi: 10.36660/abc.20200862. PMID: 33111867.

27. Ucar FM, Ozturk C, Yılmaztepe MA. Evaluation of Tp-e interval, Tp-e/QT ratio and Tp-e/QTc ratio in patients with acute myocarditis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2019 Oct 22;19(1):232. doi: 10.1186/s12872-019-1207-z. PMID: 31640548; PMCID: PMC6805629.

28. VAERSDataUseGuide_November2020

29. https://vaxopedia.org/2017/08/26/underreporting-of-side-effects-to-vaers

30. NIA Adverse Event and Serious Adverse Event Guidelines

31. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/cfrsearch.cfm?frexternal icon

32. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/fully-vaccinated-guidance.html

33. Temporary_Authorisation_Patient_Information_BNT162_7_0_UK.pdf

34. Fact Sheet for Vaccination Providers-Full EUA PI_Final_2.25.2021.pdf

35. Noa Dagan, M.D., et al. BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine in a Nationwide Mass Vaccination Setting. New England Journal of Medicine. February 24, 2021, DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2101765

36. Walsh EE, Frenck RW Jr, Falsey AR, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, Lockhart S, Neuzil K, Mulligan MJ, Bailey R, Swanson KA, Li P, Koury K, Kalina W, Cooper D, Fontes-Garfias C, Shi PY, Türeci Ö, Tompkins KR, Lyke KE, Raabe V, Dormitzer PR, Jansen KU, Şahin U, Gruber WC. Safety and Immunogenicity of Two RNA-Based Covid-19 Vaccine Candidates. N Engl J Med. 2020 Dec 17;383(25):2439-2450. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2027906. Epub 2020 Oct 14. PMID: 33053279; PMCID: PMC7583697.

37. Polack FP, et al. C4591001 Clinical Trial Group. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020 Dec 31;383(27):2603-2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. Epub 2020 Dec 10. PMID: 33301246; PMCID: PMC7745181.

38. Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center. COVID-19 dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University. 2020, CDC, WHO, Khan T, Agnihotri K, Tripathi A, Mukherjee S, Agnihotri N, Gupta G. COVID-19: A Worldwide, Zoonotic, Pandemic Outbreak. Altern Ther Health Med. 2020 Aug;26(S2):56-64. PMID: 32412918

39. IPAK Report 2021-1. 2021. Post-vaccination Death Causality Likely Given Temporal Distribution of Deaths Following COVID19 Vaccinations. Interim results.

40. Tinari S. The EMA covid-19 data leak, and what it tells us about mRNA instability BMJ 2021; 372 :n627 doi:10.1136/bmj.n627

41. Corbett, K.S., Edwards, D.K., Leist, S.R. et al. SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine design enabled by prototype pathogen preparedness. Nature 586, 567–571 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2622-0.

42. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/recommendations/specific-groups/allergies.html

43. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/info-by-product/pfizer/reactogenicity.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fvaccines%2Fcovid-19%2Finfo-by-manufacturer%2Fpfizer%2Freactogenicity.html

44. https://www.docdroid.net/xq0Z8B0/pfizer-report-japanese-government-pdf#page=17

45. Yuyang Lei, et al., SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Impairs Endothelial Function via Downregulation of ACE2. Circulation Research. April 30, 2021.

46. Gretchen Vogel, Jennifer Couzin-Frankel. Israel reports link between rare cases of heart inflammation and COVID-19 vaccination in young men. Jun. 1, 2021.

47. Johns Hopkins University of Medicine Coronavirus Resource Centre. Vaccine Research and Development. 2021

48. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/

49. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/concerns/concerns-history.html

50. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04368728

51. RW Malone, PL Felgner, IM Verma. Cationic liposome-mediated RNA transfection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) 86 (16), 6077-6081.

52. Wolff JA, Malone RW, et al. Direct gene transfer into mouse muscle in vivo. Science. 1990;247(4949 Pt 1):1465-8.

53. Siripanthong B, Nazarian S, Muser D, et al. Recognizing COVID-19-related myocarditis: The possible pathophysiology and proposed guideline for diagnosis and management. Heart Rhythm. 2020;17(9):1463-1471. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.05.001

54. Mele D, Flamigni F, Rapezzi C, Ferrari R. Myocarditis in COVID-19 patients: current problems. Intern Emerg Med. 2021 Jan 23:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s11739-021-02635-w. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33484452; PMCID: PMC7823176.

55. Liang Chen, Xiangjie Li, Mingquan Chen, Yi Feng, Chenglong Xiong, The ACE2 expression in human heart indicates new potential mechanism of heart injury among patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, Cardiovascular Research, Volume 116, Issue 6, 1 May 2020, Pages 1097–1100, https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvaa078.

56. Shant Der Sarkissian, Justin L. Grobe, Lihui Yuan, Dhruv R. Narielwala, Glenn A. Walter, Michael J. Katovich, Mohan K. Raizada. Cardiac Overexpression of Angiotensin Converting Enzyme 2 Protects the Heart From Ischemia-Induced Pathophysiology. Hypertension. 2008;51:712-718.

57. Peretto G, Sala S, Rizzo S, De Luca G, Campochiaro C, Sartorelli S, Benedetti G, Palmisano A, Esposito A, Tresoldi M, Thiene G, Basso C, Della Bella P. Arrhythmias in myocarditis: State of the art. Heart Rhythm. 2019 May;16(5):793-801. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2018.11.024. Epub 2018 Nov 24. PMID: 30476544.

58. Bishwas Chamling, Volker Vehof, Stefanos Drakos, Mareike Weil, Philipp Stalling, Christian Vahlhaus, Patrick Mueller, Michael Bietenbeck, Holger Reinecke, Claudia Meier & Ali Yilmaz. Occurrence of acute infarct-like myocarditis following COVID-19 vaccination: just an accidental co-incidence or rather vaccination-associated autoimmune myocarditis? Clinical Research in Cardiology, Received: 25 June 2021 / Accepted: 28 July 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-021-01916-w.

59. Colson P, Rolain JM, Lagier JC, Brouqui P, Raoult D. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine as available weapons to fight COVID-19. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020 Apr;55(4):105932. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105932. Epub 2020 Mar 4. PMID: 32145363; PMCID: PMC7135139.

60. Meo SA, Klonoff DC, Akram J. Efficacy of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of COVID-19. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020 Apr;24(8):4539-4547. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202004_21038. PMID: 32373993.

61. Ibáñez S, Martínez O, Valenzuela F, Silva F, Valenzuela O. Hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine in COVID-19: should they be used as standard therapy? Clin Rheumatol. 2020 Aug;39(8):2461-2465. doi: 10.1007/s10067-020-05202-4. Epub 2020 Jun 3. PMID: 32495226; PMCID: PMC7267470.

62. N, Esposito S. Chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine for prophylaxis of COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 Oct;20(10):1118. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30296-6. Epub 2020 Apr 17. PMID: 32311322; PMCID: PMC7164862.

63. Ferner RE, Aronson JK. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in covid-19. BMJ. 2020 Apr 8;369:m1432. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1432. PMID: 32269046.; Hernandez AV, Roman YM, Pasupuleti V, Barboza JJ, White CM. Hydroxychloroquine or Chloroquine for Treatment or Prophylaxis of COVID-19: A Living Systematic Review. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Aug 18;173(4):287-296. doi: 10.7326/M20-2496. Epub 2020 May 27. PMID: 32459529.;

64. Shah S, Das S, Jain A, Misra DP, Negi VS. A systematic review of the prophylactic role of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19). Int J Rheum Dis. 2020 May;23(5):613-619. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.13842. Epub 2020 Apr 27. PMID: 32281213; PMCID: PMC7262257.

65. Rizzo E. Ivermectin, antiviral properties and COVID-19: a possible new mechanism of action. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2020 Jul;393(7):1153-1156. doi: 10.1007/s00210-020-01902-5. Epub 2020 May 27. PMID: 32462282; PMCID: PMC7251046.

66. Heidary F, Gharebaghi R. Ivermectin: a systematic review from antiviral effects to COVID-19 complementary regimen. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 2020 Sep;73(9):593-602. doi: 10.1038/s41429-020-0336-z. Epub 2020 Jun 12. PMID: 32533071; PMCID: PMC7290143.

67. Sharun K, Dhama K, Patel SK, Pathak M, Tiwari R, Singh BR, Sah R, Bonilla-Aldana DK, Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Leblebicioglu H. Ivermectin, a new candidate therapeutic against SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2020 May 30;19(1):23. doi: 10.1186/s12941-020-00368-w. PMID: 32473642; PMCID: PMC7261036.

68. Shih RD, Johnson HM, Maki DG, Hennekens CH. Hydroxychloroquine for Coronavirus: The Urgent Need for a Moratorium on Prescriptions. Am J Med. 2020 Sep;133(9):1007-1008. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.05.005. Epub 2020 Jun 2. PMID: 32502485; PMCID: PMC7265864.

69. Lam S, Lombardi A, Ouanounou A. COVID-19: A review of the proposed pharmacological treatments. Eur J Pharmacol. 2020 Nov 5;886:173451. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.173451. Epub 2020 Aug 6. PMID: 32768505; PMCID: PMC7406477.

70. McCullough PA, Kelly RJ, Ruocco G, Lerma E, Tumlin J, Wheelan KR, Katz N, Lepor NE, Vijay K, Carter H, Singh B, McCullough SP, Bhambi BK, Palazzuoli A, De Ferrari GM, Milligan GP, Safder T, Tecson KM, Wang DD, McKinnon JE, O'Neill WW, Zervos M, Risch HA. Pathophysiological Basis and Rationale for Early Outpatient Treatment of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) Infection. Am J Med. 2021 Jan;134(1):16-22. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.07.003. Epub 2020 Aug 7. PMID: 32771461; PMCID: PMC7410805.

71. McCullough PA, Alexander PE, Armstrong R, Arvinte C, Bain AF, Bartlett RP, Berkowitz RL, Berry AC, Borody TJ, Brewer JH, Brufsky AM, Clarke T, Derwand R, Eck A, Eck J, Eisner RA, Fareed GC, Farella A, Fonseca SNS, Geyer CE Jr, Gonnering RS, Graves KE, Gross KBV, Hazan S, Held KS, Hight HT, Immanuel S, Jacobs MM, Ladapo JA, Lee LH, Littell J, Lozano I, Mangat HS, Marble B, McKinnon JE, Merritt LD, Orient JM, Oskoui R, Pompan DC, Procter BC, Prodromos C, Rajter JC, Rajter JJ, Ram CVS, Rios SS, Risch HA, Robb MJA, Rutherford M, Scholz M, Singleton MM, Tumlin JA, Tyson BM, Urso RG, Victory K, Vliet EL, Wax CM, Wolkoff AG, Wooll V, Zelenko V. Multifaceted highly targeted sequential multidrug treatment of early ambulatory high-risk SARS-CoV-2 infection (COVID-19). Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2020 Dec 30;21(4):517-530. doi: 10.31083/j.rcm.2020.04.264. PMID: 33387997.

72. McCullough PA, Vijay K. SARS-CoV-2 infection and the COVID-19 pandemic: a call to action for therapy and interventions to resolve the crisis of hospitalization, death, and handle the aftermath. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2021 Mar 30;22(1):9-10. doi: 10.31083/j.rcm.2021.01.301. PMID: 33792243.

73. Ioannidis, J.P. (2021), Reconciling estimates of global spread and infection fatality rates of COVID‐19: an overview of systematic evaluations. Eur J Clin Invest. Accepted Author Manuscript e13554. https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.13554

74. Noh J, Danuser G (2021) Estimation of the fraction of COVID-19 infected people in U.S. states and countries worldwide. PLoS ONE 16(2): e0246772. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246772

75. Toor SM, Saleh R, Sasidharan Nair V, Taha RZ, Elkord E. T-cell responses and therapies against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Immunology. 2021 Jan;162(1):30-43. doi: 10.1111/imm.13262. Epub 2020 Oct 27. PMID: 32935333; PMCID: PMC7730020.

76. Robbiani DF, et al. Convergent antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in convalescent individuals. Nature. 2020 Aug;584(7821):437-442. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2456-9. Epub 2020 Jun 18. PMID: 32555388; PMCID: PMC7442695.

77. Sun B, et al. Kinetics of SARS-CoV-2 specific IgM and IgG responses in COVID-19 patients. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020 Dec;9(1):940-948. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1762515. PMID: 32357808; PMCID: PMC7273175.

78. Le Bert N, et al. SARS-CoV-2-specific T cell immunity in cases of COVID-19 and SARS, and uninfected controls. Nature. 2020 Aug;584(7821):457-462. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2550-z. Epub 2020 Jul 15. PMID: 32668444.

79. Mateus J, et al. Selective and cross-reactive SARS-CoV-2 T cell epitopes in unexposed humans. Science. 2020 Oct 2;370(6512):89-94. doi: 10.1126/science.abd3871. Epub 2020 Aug 4. PMID: 32753554; PMCID: PMC7574914.

80. Lipsitch M, Grad YH, Sette A, Crotty S. Cross-reactive memory T cells and herd immunity to SARS-CoV-2. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020 Nov;20(11):709-713. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-00460-4. Epub 2020 Oct 6. PMID: 33024281; PMCID: PMC7537578.

81. Corbett, K.S., Edwards, D.K., Leist, S.R. et al. SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine design enabled by prototype pathogen preparedness. Nature 586, 567–571 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2622-0.

82. Zimmermann P, Curtis N. Factors That Influence the Immune Response to Vaccination. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019 Mar 13;32(2):e00084-18. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00084-18. PMID: 30867162; PMCID: PMC6431125.

83. Orenstein WA, Bernier RH, Dondero TJ, Hinman AR, Marks JS, Bart KJ, Sirotkin B. Field evaluation of vaccine efficacy. Bull World Health Organ. 1985;63(6):1055-68. PMID: 3879673; PMCID: PMC2536484.

84. Furman D, Davis MM. New approaches to understanding the immune response to vaccination and infection. Vaccine. 2015 Sep 29;33(40):5271-81. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.06.117. Epub 2015 Jul 29. PMID: 26232539; PMCID: PMC4581990.

85. Vaidyanathan R, O'Connell RP, Deo M, et al. The ionic bases of the action potential in isolated mouse cardiac Purkinje cell. Heart Rhythm. 2013;10(1):80-87. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.10.002.

86. Singer ME, Taub IB, Kaelber DC. Risk of Myocarditis from COVID-19 Infection in People Under Age 20: A Population-Based Analysis. medRxiv [Preprint]. 2021 Jul 27:2021.07.23.21260998. doi: 10.1101/2021.07.23.21260998. PMID: 34341797; PMCID: PMC8328065.

87. Myocarditis and Pericarditis After Vaccination for COVID-19. JAMA Published online August 4, 2021. American Medical Association.

88. Kim HW, Jenista ER, Wendell DC, Azevedo CF, Campbell MJ, Darty SN, Parker MA, Kim RJ. Patients With Acute Myocarditis Following mRNA COVID-19 Vaccination. JAMA Cardiol. 2021 Jun 29:e212828. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2021.2828. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34185046; PMCID: PMC8243258.

89. Shaw KE, Cavalcante JL, Han BK, Gössl M. Possible Association Between COVID-19 Vaccine and Myocarditis: Clinical and CMR Findings. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021 Jun 16:S1936-878X(21)00485-X. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2021.06.002. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34246586; PMCID: PMC8245050.

90. Mei R, Raschi E, Forcesi E, Diemberger I, De Ponti F, Poluzzi E. Myocarditis and pericarditis after immunization: Gaining insights through the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System. Int J Cardiol. 2018 Dec 15;273:183-186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.09.054. Epub 2018 Sep 14. PMID: 30236504.

91. Das BB, Moskowitz WB, Taylor MB, Palmer A. Myocarditis and Pericarditis Following mRNA COVID-19 Vaccination: What Do We Know So Far? Children (Basel). 2021 Jul 18;8(7):607. doi: 10.3390/children8070607. PMID: 34356586; PMCID: PMC8305058.Hudson B, Mantooth R, DeLaney M. Myocarditis and pericarditis after vaccination for COVID-19. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021 Jul 26;2(4):e12498. doi: 10.1002/emp2.12498. PMID: 34337595; PMCID: PMC8313036.

92. Luk A, Clarke B, Dahdah N, Ducharme A, Krahn A, McCrindle B, Mizzi T, Naus M, Udell JA, Virani S, Zieroth S, McDonald M. Myocarditis and Pericarditis following COVID-19 mRNA Vaccination: Practical Considerations for Care Providers. Can J Cardiol. 2021 Aug 7:S0828-282X(21)00624-3. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2021.08.001. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34375696; PMCID: PMC8349442

93. Vidula MK, Ambrose M, Glassberg H, Chokshi N, Chen T, Ferrari VA, Han Y. Myocarditis and Other Cardiovascular Complications of the mRNA-Based COVID-19 Vaccines. Cureus. 2021 Jun 10;13(6):e15576. doi: 10.7759/cureus.15576. PMID: 34277198; PMCID: PMC8270057

94. Dionne A, Sperotto F, Chamberlain S, Baker AL, Powell AJ, Prakash A, Castellanos DA, Saleeb SF, de Ferranti SD, Newburger JW, Friedman KG. Association of Myocarditis With BNT162b2 Messenger RNA COVID-19 Vaccine in a Case Series of Children. JAMA Cardiol. 2021 Aug 10:e213471. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2021.3471. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34374740; PMCID: PMC8356143.

95. Montgomery J, Ryan M, Engler R, Hoffman D, McClenathan B, Collins L, Loran D, Hrncir D, Herring K, Platzer M, Adams N, Sanou A, Cooper LT Jr. Myocarditis Following Immunization With mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines in Members of the US Military. JAMA Cardiol. 2021 Jun 29:e212833. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2021.2833. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34185045; PMCID: PMC8243257.

96. Imazio M, Klingel K, Kindermann I, Brucato A, De Rosa FG, Adler Y, De Ferrari GM. COVID-19 pandemic and troponin: indirect myocardial injury, myocardial inflammation or myocarditis? Heart. 2020 Aug;106(15):1127-1131. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2020-317186. Epub 2020 Jun 4. PMID: 32499236.

97. Fatmi SS, Basso R, Liaqat A, Tariq F, Swamiappan R. COVID-19 Myocarditis: Rationale for Early Diagnosis and Intervention. Cureus. 2021 Jul 19;13(7):e16494. doi: 10.7759/cureus.16494. PMID: 34430109; PMCID: PMC8373509.

98. Salah HM, Mehta JL. COVID-19 Vaccine and Myocarditis. Am J Cardiol. 2021 Jul 12:S0002-9149(21)00639-1. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2021.07.009. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34399967; PMCID: PMC8272967.

99. Singh B, Kaur P, Cedeno L, Brahimi T, Patel P, Virk H, Shamoon F, Bikkina M. COVID-19 mRNA Vaccine and Myocarditis. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2021 Jun 14;8(7):002681. doi: 10.12890/2021_002681. PMID: 34268277; PMCID: PMC8276934.

100. Bozkurt B, Kamat I, Hotez PJ. Myocarditis With COVID-19 mRNA Vaccines. Circulation. 2021 Aug 10;144(6):471-484. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.056135. Epub 2021 Jul 20. PMID: 34281357; PMCID: PMC8340726.

Thank you for your tenacity and hard work--you’re an inspiration to so many! 🙏🏽

I can't help but think about the agenda behind it all. Why after the reporting of so many adverse events, especially in the child and working-age groups, are these shots not pulled from the market? Considering the FDA just approved the Ba-5 bivalent booster based on a failed trial of 8 mice. All got Covid, their antibody titers were all over the place, and all were killed before any longer term effects could be determined. That's not science, that's quackery; yet, they want humanity to roll up their sleeves and continue to take the poison. In Canada, the government wants people to take boosters every 90 days. Why, for goodness sake?!